Appendix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

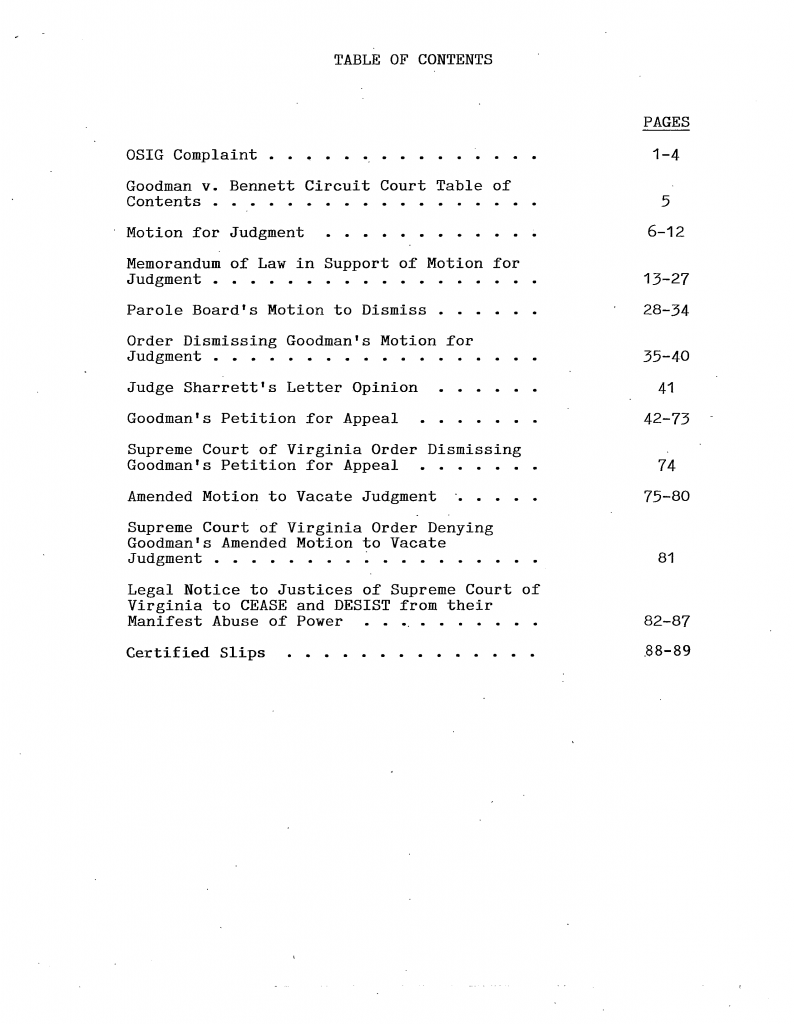

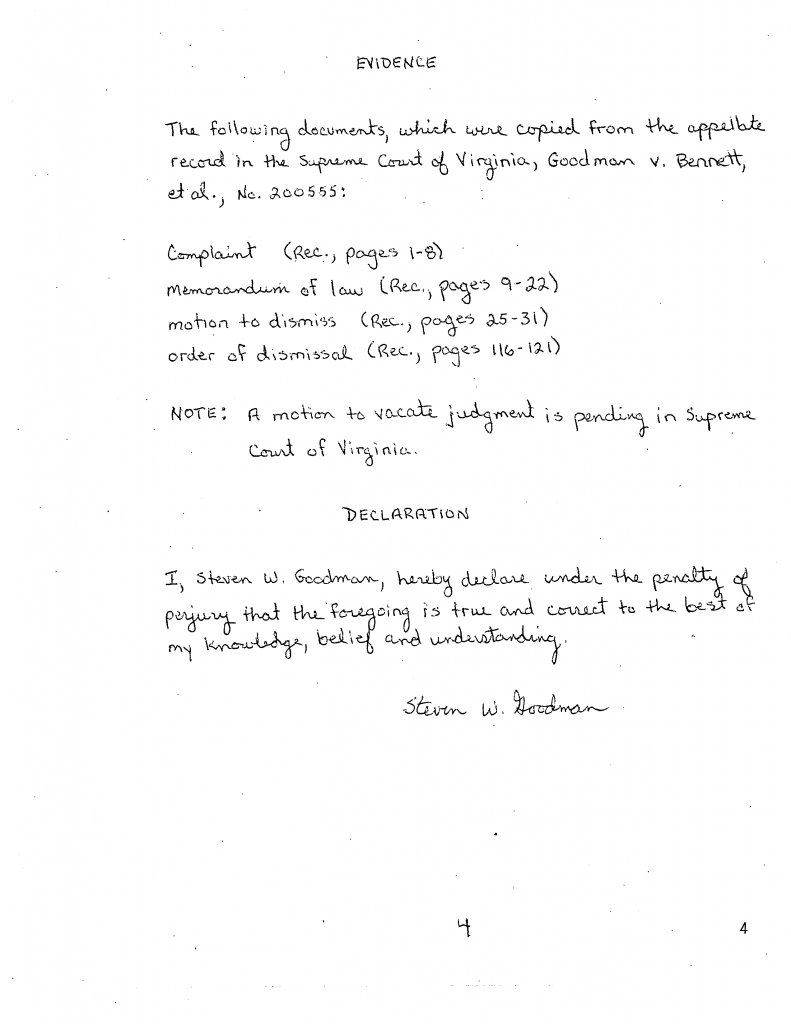

Page 1-4: OSIG Complaint

Page 5: Goodman v. Bennett Circuit Court Table of Contents

Page 6-12: Motion for Judgment

Page 13-27: Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion for Judgment .

Page 28-34: Parole Board’s Motion to Dismiss

Page 35-40: Order Dismissing Goodman’s Motion for Judgment

Page 41: Judge Sharrett’s Letter Opinion

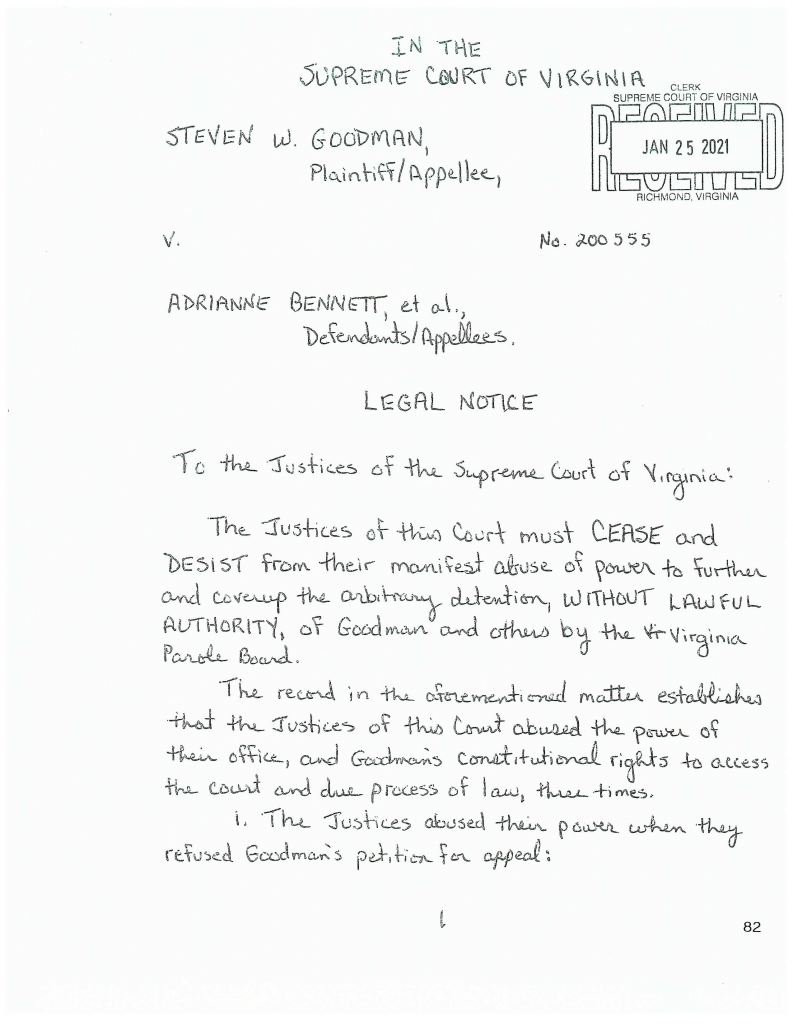

Page 42-73: Goodman’s Petition for Appeal

Page 74: Supreme Court of Virginia Order Dismissing Goodman’s Petition for Appeal

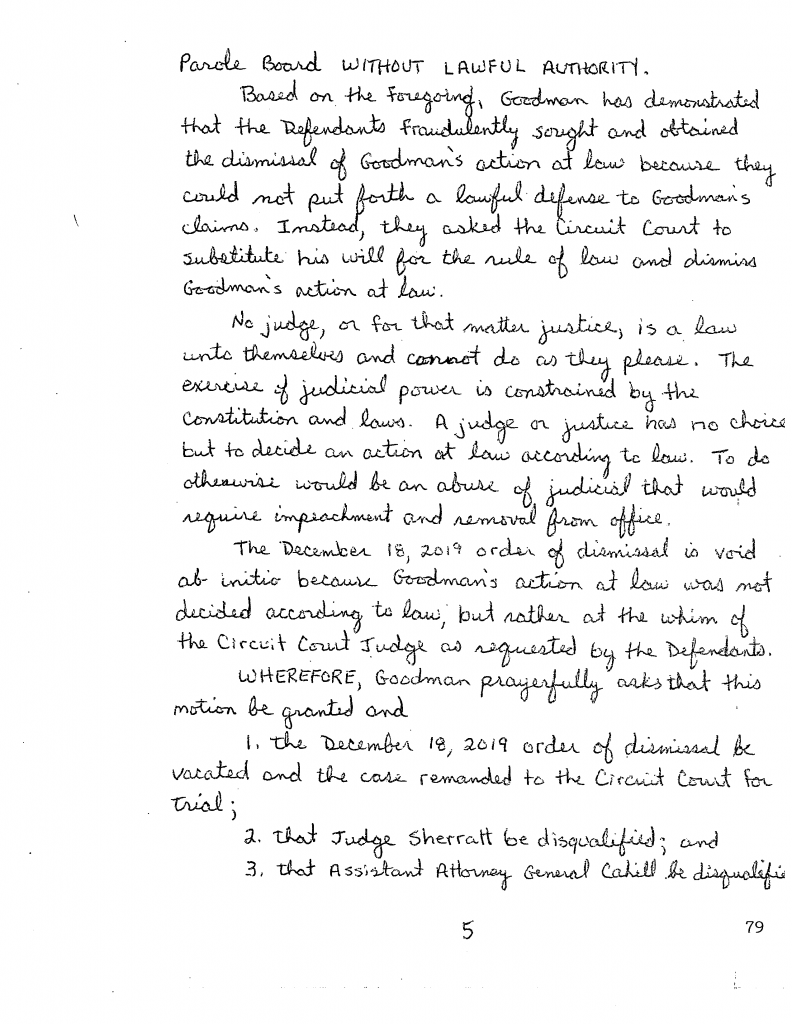

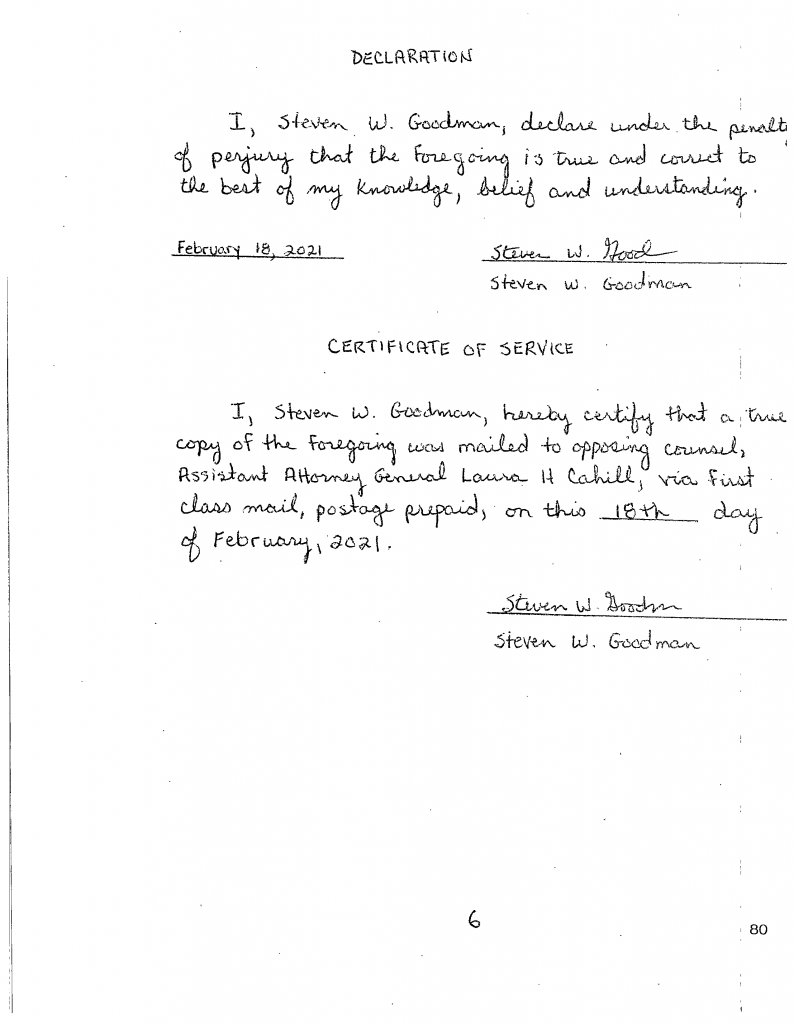

Page 75-80: Amended Motion to Vacate Judgment

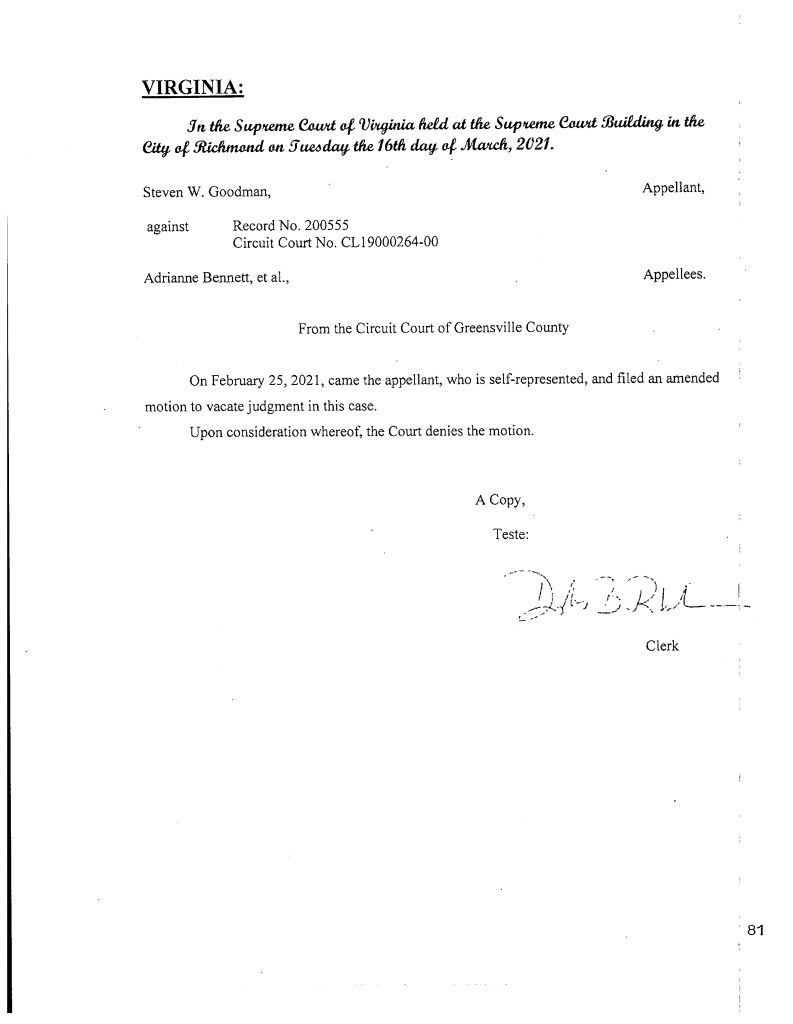

Page 81: Supreme Court of Virginia Order Denying Goodman’s Amended Motion to Vacate Judgment

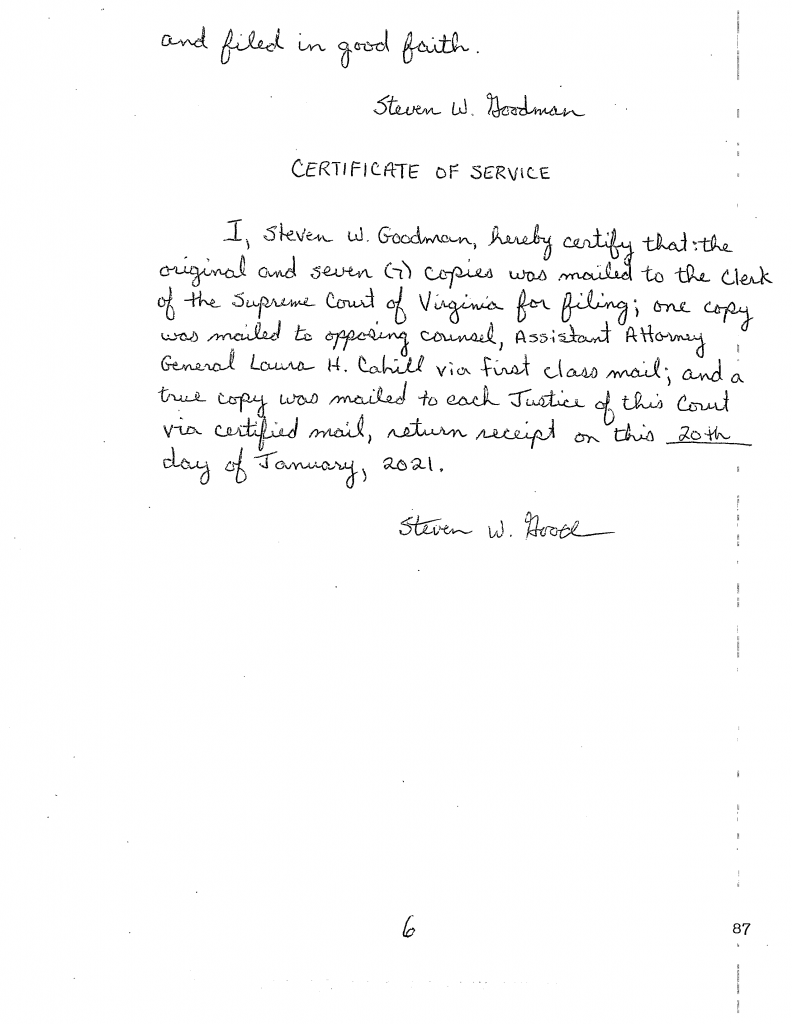

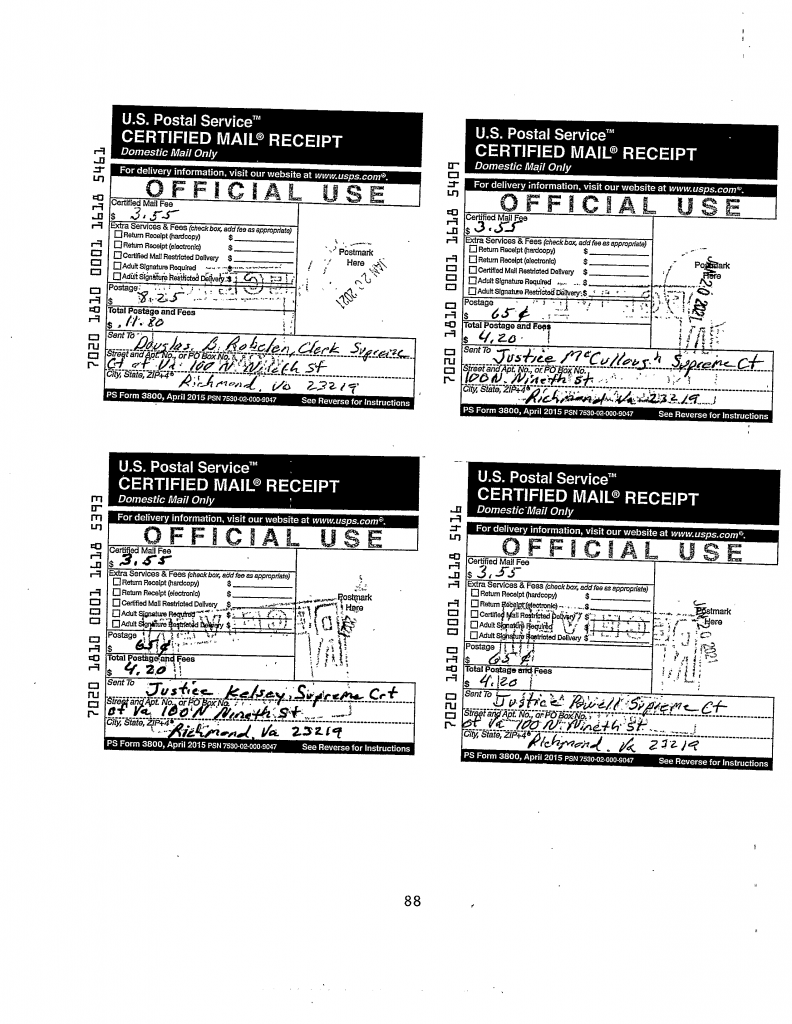

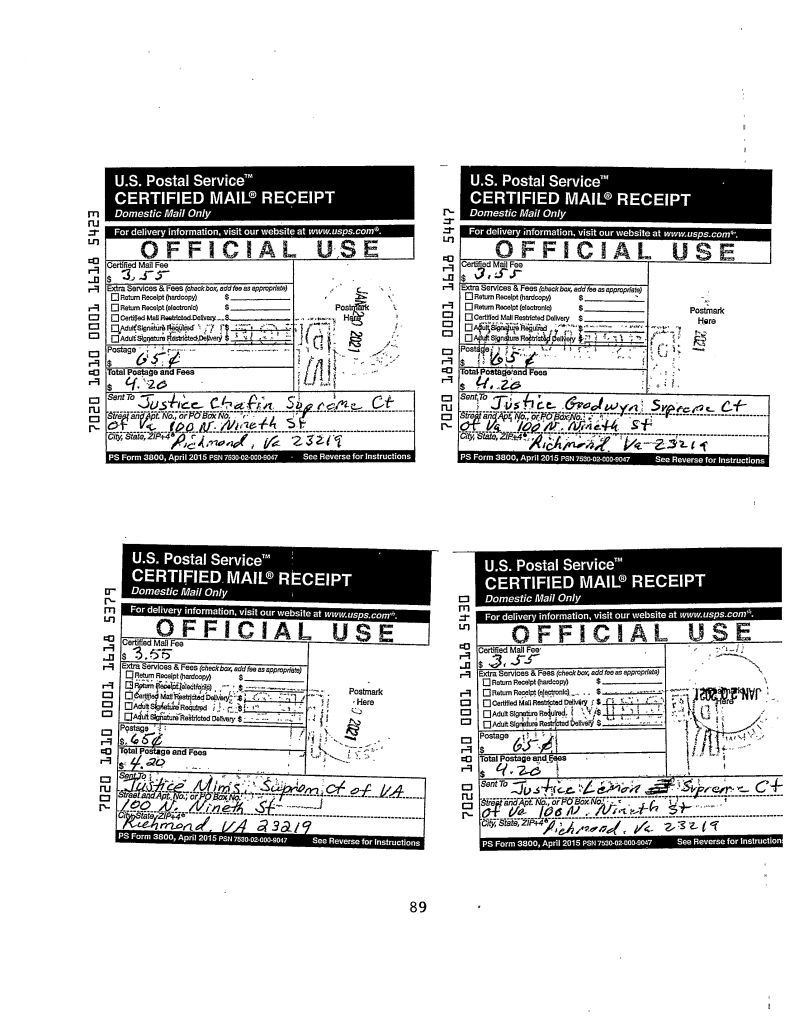

Page 88-89: Certified Slips

Appendix

Conservatives love to denigrate liberal judges as “judicial activists” who read into the Constitution rights that do not appear in the text (i.e. abortion rights). Conservative judges, on the other hand, are tyrants who have empowered themselves, through the creation of a cost-benefit constitutional analysis, to determine on a case-by-case basis who shall enjoy the benefit of a constitutional right. They wield this power as an instrument of oppression against criminal defendants who are mostly persons of color. In fact, conservative judges also manipulate the facts and law to make a case turn out the way they want, and have created no-publication-and no-citation rules to cover up these abuses.

SUPREME COURT JUSTICES USURP LEGISLATIVE POWER

TO UNLAWFULLY AMEND THE FOURTH AMENDMENT

The Framers knew that the accumulation of all powers, Legislative, Executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many,’ and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.’ In order to prevent such tyranny, the Framers devised a governmental structure composed of three distinct branches–a vigorous Legislative Branch, a separate and wholly independent Executive Branch, and a Judicial Branch equally independent. The separation of powers and the checks and balances that the Framers built into our tripartite form of government were intended to operate as a self-executing safeguard against the encroachment or aggrandizement of one branch at the expense of the other. The fundamental necessity of maintaining each of the three general departments of government entirely free from control or coercive influence, direct or indirect, of either of the others, has often been stressed and is hardly open to serious question. Commodity Futures Trading Com v. Schor, 478 U.S. 833, 859-860 (1986) (quotation marks, internal quotation marks, alterations, and citations omitted).

The separation of powers is designed to preserve the liberty of all the people. So whenever a separation-of-powers violation occurs, any aggrieved party with standing may file a constitutional challenge. Collins v. Yellen, 141 S.Ct. 1761, 1780 (2021) (internal quotes, quotation marks, and citations omitted).

The United States Supreme Court has usurped legislative power, in violation of the separation of powers doctrine, to illegally amend the Fourth Amendment. In doing so, they transformed the Fourth Amendment from a protected constitutional right to a mere privilege that is subject to the whim of judges.

The Fourth Amendment states as follows:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers,’ and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants-shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. (Emphasis added).

Words matter. Congress used the word “shall” in the enforcement clause of the Fourth Amendment.’ The word “shall” is a mandatory term that deprives the courts of any discretion in the manner in which the Fourth Amendment is to be interpreted or enforced. As such, evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment cannot be used at trial; to hold otherwise would reward the government for their violation, and further encourage and allow them to continue to violate the Fourth Amendment.

Since the Fourth Amendment was enacted, the Supreme Court has created the exclusionary rule to exclude evidence from the trial that was obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment. This rule, which is inferred from the enforcement clause, “shall not be violated,” is the only means available to give meaning to this clause, and is necessary to enforce this constitutional right.

Over time, the Supreme Court created several exceptions to the exclusionary rule. In addition, they created a costs benefit constitutional analysis in which they weigh the costs to society versus the enforcement of the Fourth Amendment.

In Stone v. Powell, 428 U.S. 465, 482 (1976), the United States Supreme Court held: “[W]here the State has provided an opportunity for full and fair litigation of a Fourth Amendment claim, the Constitution does not require that a state prisoner be granted federal habeas corpus relief on the ground that evidence obtained/in an unconstitutional search or. seizure was introduced at his trial.”

In reaching this decision, six, conservative, white, male, Justices considered the “costs of applying the exclusionary rule even at trial and on direct review.” Id., at 489. These societal costs included:

- “the focus of the trial, and the attention of the participants therein, are diverted from the ultimate question of guilt or innocence.” Id.

- “the physical evidence sought to be excluded is typically reliable and often the most probative information bearing on guilt or innocence of the defendant.” Id.

- “ordinarily the evidence seized can in no way have been rendered untrustworthy by the means of its seizure and indeed often this evidence alone establishes beyond virtually any shadow of a doubt that the defendant is guilty.” Id.

- The disparity in particular cases between the errors committed by the police officer and the winfall afforded a guilty defendant by application of the rule is contrary to the idea of proportionality that is essential to the concept of justice.” Id.

- “Although the rule is thought to deter unlawful police activity in part through the nurturing of respect for Fourth Amendment values, if applied indiscriminately it may well have the opposite effect of generating disrespect for the law and administration of justice.” Id., at 491.

- “the public interest in prosecuting those accused of crime and having them acquitted or convicted on the basis of all the evidence which exposes the truth. Id., at 491.

The Court further added: “These long recognized costs of the rule persist when a criminal conviction is sought to be overturned on [a federal habeas corpus proceeding] on the ground that a search and seizure claim was erroneously rejected by two or more tiers of state courts.” Id.

In sum, these six, conservative, white, male Justices concluded that the costs to society outweighed the benefits of allowing state prisoners to raise Fourth Amendment claims in a federal habeas corpus petition, even if the issue “was erroneously rejected by two or more tiers of state courts.” Id.

Based upon Congress’s use of the word “shall” in the Fourth Amendment enforcement clause, the majority in Stone, and those before and after them, violated their oath of office by exercising discretion that they did not have. If Congress had wanted the courts to have discretion in the manner in which the Fourth Amendment is enforced, they “could have easily substituted ‘may’, for ‘shall’” in the Fourth Amendment. Murphy v. Smith, 138 U.S. 784, 787 (2018). The word “may” is a permissive word that would have given the courts discretion.

In his dissent, with whom Justice Marshall concurred, Justice Brennan concluded that the Court’s “constitutional ‘interest balancing’ approach to this case is untenable, and I can only view the constitutional garb in which the Court dresses its result as a disguise for rejection of the longstanding principle that there are no ‘second class’ constitutional rights for purposes of federal habeas jurisdiction; it is nothing less than an attempt to provide a veneer of respectability for an obvious usurpation of Congress’ Art. III power to delineate the jurisdiction of the federal courts.” Id., at 515.

CONCLUSION

Based on the foregoing, it is beyond any doubt that the six, conservative, white, male Justices in Stone, and those before and after them, did in fact usurp legislative power when they granted themselves discretion, which the text of the Fourth Amendment specifically prohibits; in the manner in which the Fourth Amendment is to be enforced. In doing so, they effectively amended the Fourth Amendment enforcement clause by replacing the mandatory term “shall” with the permissive term “may” to grant themselves discretion.

POLITICIZATION OF CONSTITUTION BY CONSERVATIVE JUSTICES

The politicization of the Constitution by conservative Justices is self-evident when you compare the manner in which they interpret the Second and Fourth Amendments. As previously set forth, conservative Supreme Court Justices created a cost-benefit constitutional analysis to determine whether the costs to society outweigh the benefits of enforcing the Fourth Amendment. In regards to the Second Amendment, conservative Justices refused to use this same “interest balancing” test. Stone, at 488, 515.

In District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 634 (2008), Justice Scalia, writing for the Court, addressed an argument Justice Breyer made in his dissent saying: He criticizes us for declining to establish a level of scrutiny for evaluating Second Amendment restrictions. He proposes explicitly at least, none of the traditionally expressed levels (strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny, rational basis), but rather a judge-empowering ‘interest balancing inquiry’ [that] asks whether the statute burdens a protected interest in a way or to an extent that is out of proportion to the statute’s salutary effects upon other important governmental interests.” Id., at 634.

Justice Scalia further said: We know of no other enumerated constitutional right whose core protection has been subjected to a freestanding ‘interest balancing’ approach.” Id. This statement is unequivocally false. Conservative Supreme Court Justices have repeatedly used an “‘Interest balancing’ approach” (i.e. public safety) to illegally transform the Fourth Amendment from a protected constitutional right to a mere privilege subject to the whim • of judges.

Ironically, Justice Scalia aptly described the danger and destruction brought to a constitutional right through the use of an “interest balancing” test: “The very enumeration of the right takes out of the hands of government–even the Third Branch of Governments—the power to decide on a case-by-case basis whether the right is really worth insisting upon. A constitutional guarantee subject to future judges’ assessments of its usefulness is no constitutional right at all.” Id. Yet, this is exactly what conservative judges have done to the Fourth Amendment.

Finally, it must be noted that Congress used almost identical language in the enforcement clause of the Second and Fourth Amendments: Second Amendment: “shall not be infringed;” and Fourth Amendment: “shall not be violated.” The words “infringed” and “violated” are synonymous.

RACIAL MOTIVE

Less than four years after the enactment of the Civil Rights Act, President Nixon declared his “war on drugs” a few days after taking office in I969. At this time, the drug problem was largely an inner-city problem, or more specifically a problem in the black community. Just eight years later, the Supreme Court, in Stone v. Powell, held that state prisoners could not raise a Fourth Amendment claim in a federal habeas corpus proceeding, even if the issue was decided wrongly in the state courts. In sum, this decision encouraged and allowed the states to violate the Fourth Amendment, and to use evidence obtained in violation thereof at trial. As Justice Scalia stated in his majority opinion, it was more important to obtain criminal convictions than it is to vindicate constitutional rights. See pages 4-5.

In sum, Nixon’s “war on drugs” was a war against the black community, and the Stone v. Powell decision was made to make it easier to lock up black people.

CONCLUSION

Based on the foregoing, it is beyond any doubt that conservative Justices have an actual bias against those charged with a crime. Justice Scalia’s opinion makes it clear that obtaining criminal ‘convictions is more important than any constitutional right. When Scalia’s Stone opinion is put into historical context, it becomes clear that it was designed to oppress the constitutional rights of persons of color to aid President Nixon’s war on the black community.

NO-PUBLICATION AND NO-CITATION RULES

It is well known or certainly believed, that the United States has a two-tier system of justice: one system for whites and one system for blacks. The problem is that no one has been able to identify what that means or how to redress it.

The answer is simple. The courts keep two sets of books: published and unpublished. Published opinions can be found in books for all the world to see how just and fair our judicial system is. Unpublished opinions remain in court files and are not readily available to read. The reason for these no publication and no citation rules is to further cover up the systemic abuse of judicial power, particularly in criminal cases, where the courts manipulate, the facts and law to make a case turn out the way they desire.

A crooked accountant keeps two sets of books: One set of books shows the account as it’s supposed to be; the other set of books shows the account as it really is. The first set of books is shown to the boss so as not to raise any suspicion. The other set of books the accountant keeps to himself so that he can manage his embezzlement in a way that does not cause alarm. The courts are doing the same thing as the crooked accountant with their two sets of books.

On May 24, 1989, Professor Monroe Freedman gave a speech at the Seventh Annual Judicial Conference of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Professor Freedman excoriated the judges in this Nation’s second highest court for their manipulation of facts and law to make a case turn out the way they want, and their creation and use of non-publication and no-citation rules to cover up their abuse.

In his speech, Professor Freedman said:

Frankly, I have had more than enough of judicial opinions that bear no relationship whatsoever to the cases that have been filed and argued before the judges. I am talking about judicial opinions that falsify the facts of cases that have been argued, judicial opinions that make disingenuous use or omission of material authorities, judicial opinions that cover up these things with no-publication and no-citation rules. Correspondence: Self-Regulation of Judicial Misconduct Could be Mis-Regulation, 89 Mich. L. Rev. 609, 619-620; also reprinted in 128 F.R.D. 409, 439 (1989).

At the luncheon immediately following the speech, the judge sitting next to Professor Freedman said: “You don’t know the half of it.” Id. This judge agreed with Professor Freedman and said the problem was far worse. While this speech was given 33 years ago, the courts still use no-publication and no-citation rules, and for the same reasons.

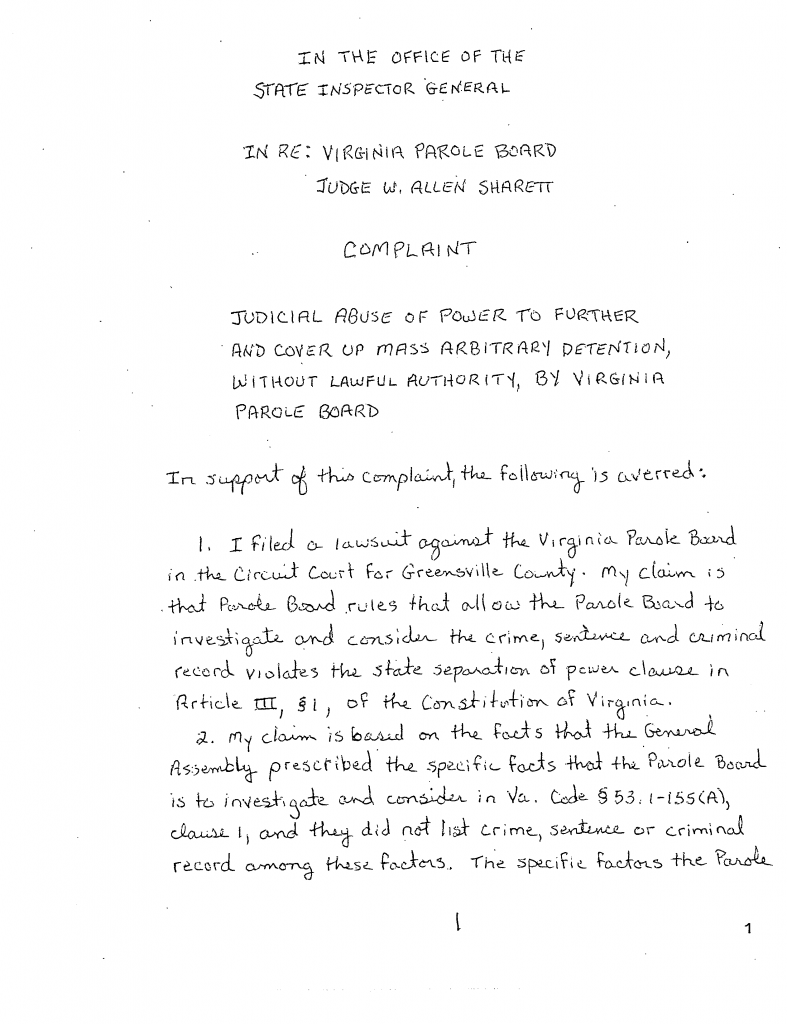

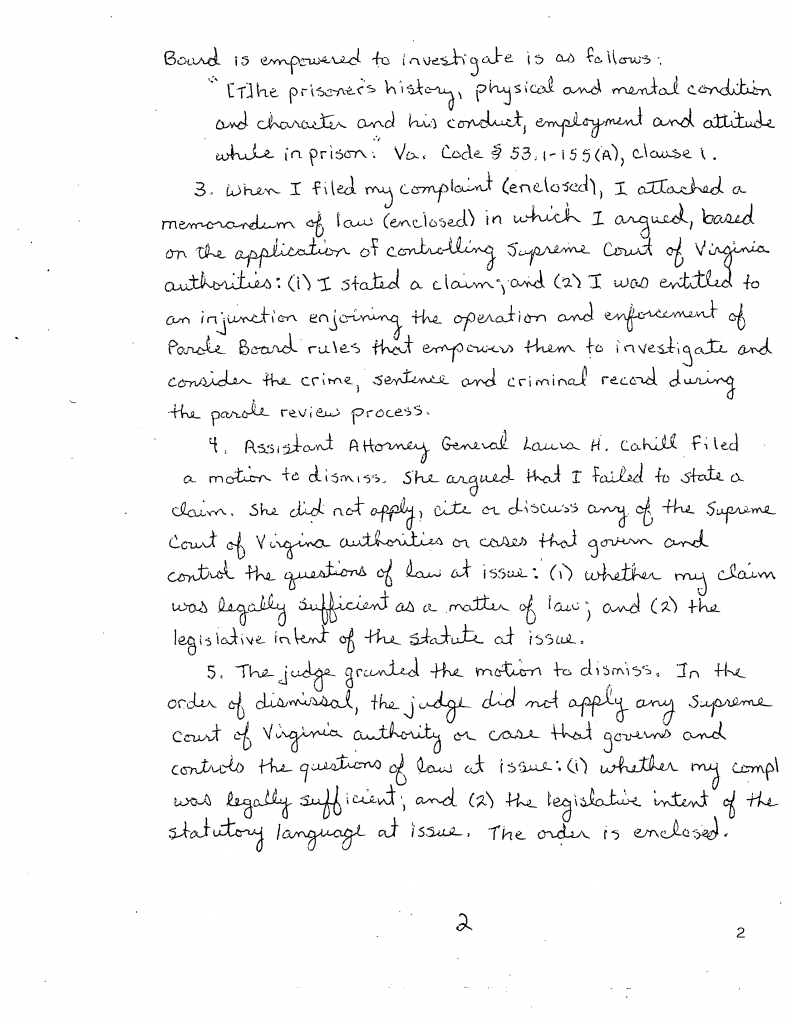

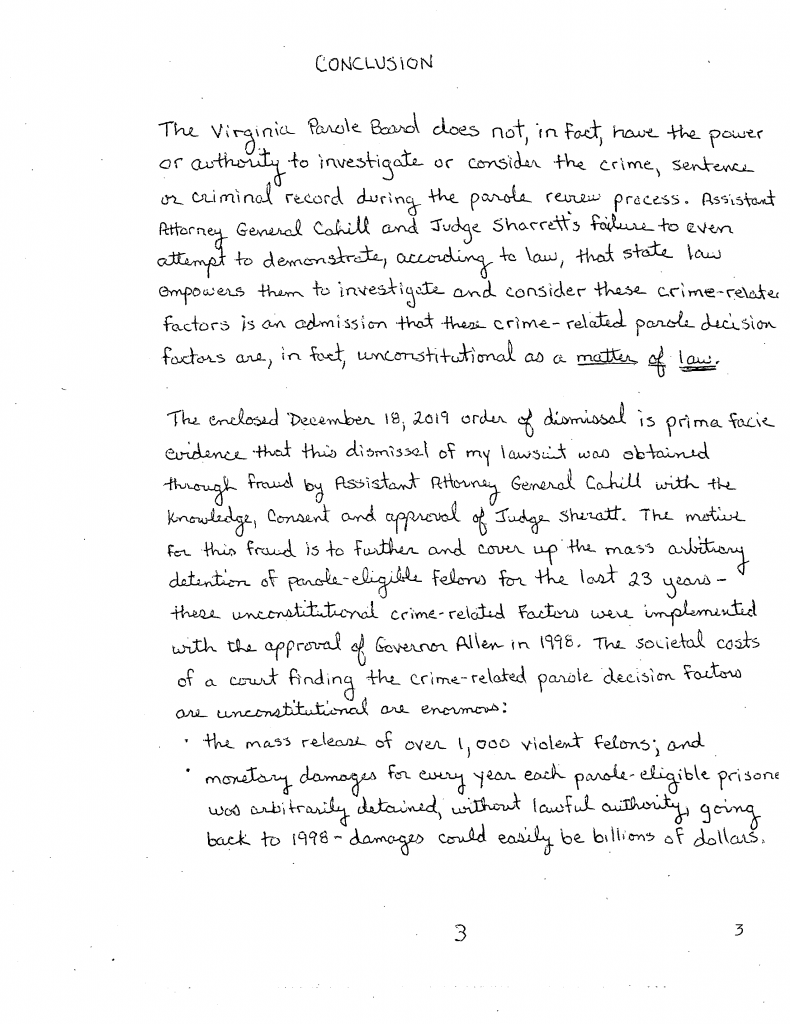

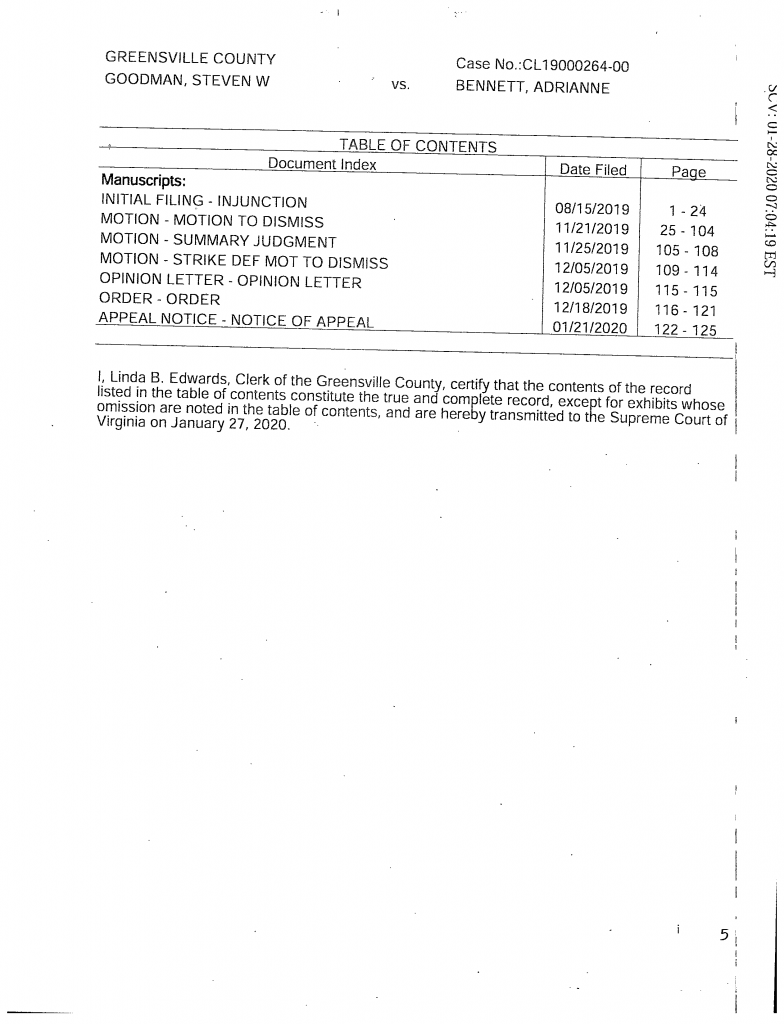

CASE STUDY: GOODMAN V. BENNETT

In Goodman v. Bennett, Steve Goodman, a parole-eligible Link prisoner in Virginia, filed a state lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of certain Parole Board rules as violative of the state separation of power clause, Article III, § 1, of the Constitution of Virginia. Goodman raised the following novel claim:

Whether the Parole Board has the power to investigate or consider the crime, sentence, or criminal record during the parole review process.

At first blush, the answer would seem to be yes: The Parole Board almost always denies parole for crime-related reasons, which the courts say is constitutional, so they must have the power to investigate these crime-related factors. In any regard, the answer must be found within the statutes the Board is charged with enforcing.

In Virginia, the law mandates that the Parole Board “shall” release on parole “eligible [prisoners]” when those persons are found “suitable for parole.” Va. Code § 53.1-136(3)(a). In addition, the General Assembly enacted statutory procedures (Va. Code § 53.1-151 to 53.1-165.1) to govern and control the manner in which the Board exercise’s its discretion. These statutory procedures create a liberty interest for parole-eligible prisoners.

In § 53.1-151, the General Assembly used the crime, sentence, and criminal record, and other crime-related factors to establish parole eligibility criteria. Gaston v. Taylor, 946 F.2d 340, 344 (4th Cir. 1991). The parole-eligibility criteria is self-executing. The Parole Board has no discretion regarding parole eligibility; instead, they have a ministerial duty to apply this criterion correctly. Krawetz v. Murray, 742 F.Supp. 304, 306 (E.D.Va. 1990).

In Va. Code § 53.1-155(A), the General Assembly established a statutory procedure to govern and control the manner, in which the Parole Board reviews eligible prisoners for parole, as it relates to the decision to grant or deny parole. This parole review process consists of two parts: investigation and decision processes. This statutory procedure establishes the following standards, which are required by the Constitution of Virginia, for each of these processes:

PAROLE INVESTIGATION STANDARD

No person shall be released on parole by the Board until a thorough investigation has been made into the prisoner’s history, physical and mental condition and character and his conduct, employment and attitude while in prison. Va. Code § 53.1-155(A), clause 1 (emphasis added).

PAROLE DECISION STANDARD

The Board shall also determine that his release on parole will not be incompatible with the interests of society or of the prisoner. Va. Code § 53.1-155(A), clause 2 (emphasis added).

PAROLE BOARD’S CRIME-RELATED PAROLE DECISION FACTORS

VIOLATE STATE SEPARATION OF POWER CLAUSE

The parole investigation standard limits the scope of the parole investigation to seven (7) factors, and the General Assembly’s use of the terms “prisoner” and “while in prison” further limits the parole investigation to that period of time in which the “prisoner’s…” in prison.” The General Assembly could have included the crime, sentence, criminal record, or any other factor, but they chose not to do so. Instead, they chose to use the crime, sentence, and criminal record to establish parole eligibility criteria in Va. Code § 53.1-151.

The parole decision standard merely defines the nature of the parole decision as a “compatibility” determination; it does not empower the Parole Board to consider any information obtained from any source other than the parole investigation prescribed in the preceding clause.

Based on the foregoing, the Parole Board cannot lawfully deny parole for any crime-related factor because the crime, sentence, and criminal record are beyond the scope of the parole investigation prescribed in Va. Code § 53.1-155(A), clause 1. As such, the Parole Board’s crime-related parole decision factors, set forth in Part I of the Parole Board Policy Manual, violate the state separation of power clause in Article III, §1, of the Constitution of Virginia, and cannot be enforced.

CONSERVATIVE VIRGINIA JUDGE AND JUSTICES ABUSE POWER

TO FURTHER AND COVER UP MASS ARBITRARY DETENTION

OF PAROLE-ELIGIBLE PRISONERS BY PAROLE BOARD

When Goodman filed his lawsuit, he attached a memorandum of law in which he argued, through the application of relevant and controlling precedents from the Supreme Court and Court of Appeals of Virginia, respectively; (1) he stated a claim; and (2) he was entitled, as a matter of law, to an injunction enjoining the operation and enforcement of the Parole Board’s crime-related (parole decision factors) rules.

The judge entered a one-sentence “letter opinion” dismissing Goodman’s lawsuit for failure to state a claim. The Judge did not acknowledge or address Goodman’s legal arguments, nor did he apply, cite or discuss any precedents from the Supreme Court of Virginia, or any other state or federal court, in his letter opinion or subsequent order for dismissal.

Similarly, the Supreme Court of Virginia affirmed the dismissal of Goodman’s lawsuit and denied his motion to vacate the void judgment, in one sentence orders. Like the Judge, the Supreme Court did not acknowledge Goodman’s legal arguments, nor did they apply, cite, or discuss any precedents from their court or any other court.

The state and federal due process of law clauses, by their very terms, mandates that courts shall decide cases according to law. In addition, several provisions in the Canons of Judicial Conduct in the Commonwealth of Virginia require Judges to: “comply with the law” (Canon 2(A)), “be faithful to the law” (Canon 3(B)(2)), and “accord to every person who has a legal interest in a proceeding, or that persons lawyer the right to be heard according to law” Canon 3(B)(7)).

It is beyond any doubt, based upon the orders and opinions of the Judge and Justices in court records, and the .pleadings and papers Goodman filed in both courts, that: (1) Goodman raised significant legal arguments, supported by precedents by the Supreme Court and Court of Appeals of Virginia, challenging the constitutionality of specific Parole Board rules; and (2) the Judge and Justices abandoned their constitutional and professional duty to decide Goodman’s case according to law, and substituted their whim and will in its place.

In his article, Judicial Independence in the United States” 40 St. Louis L. J. 989, (former) Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer discussed this issue in his very first sentence:

The question of judicial independence revolves around the theme of how to assure that judges decide according to the law, rather than according to their own whims or to the will of the political branches of government.

In his closing, Justice Breyer reiterated the importance of Judges deciding cases according to the law in more stark terms:

Justice and stability of a country is only attainable, however, if judges actually decide according to law, and are perceived by everyone around them to be deciding according to law, rather than according to their own whim or in compliance with the will of powerful political actors.

There have been many other articles written that addressed the professional duty of judges to decide according to law. In the article, “Judicial Independence: Is it Impaired or Bolstered by Judicial Accountability?, 84 St. John’s L, Rev. 1, 14-5, the author explained how a judge can be “independent and honorable” or “independent and accountable:”

To do so, a judge “shall,” among other things , respect and comply with the law, “be faithful to the law and maintain professional competence in it, ” perform judicial duties without bias or prejudice against or in favor of any person, and “accord to every person who has a legal interest in the proceeding, or that person’s lawyer, the right to be heard according to law, These standards envisage a jurist as the guardian of the public’s legal rights and presume that judges will remain tethered to legal principles when exercising decisional independence.

When this manifest abuse of judicial power is put in the proper context, it becomes clear that this is the judicial equivalent of George Floyd’s murder–the Judge and Justices snuffed out Goodman’s constitutional rights–and the orders and opinions they rendered are equivalent to the videos of George Floyd’s murder. Moreover, their motive is truly frightening: to further and cover up the mass arbitrary detention of parole-eligible prisoners, without lawful authority, by the Parole Board.

Obviously, these courts used a constitutional ‘interest balancing” test that was created by conservative Justices in the Supreme Court. They concluded that the costs to society outweighed the benefits of upholding Goodman’s constitutional rights. These “costs” would have included: declaring that the investigation, consideration, and use of Goodman’s crime, sentence, and criminal record are beyond the scope of the statutory parole review process; this would have resulted in the mass release of over 1,000 parole-eligible prisoners; and Virginia would have to pay enormous monetary damages, likely over one billion dollars, for each year parole-eligible prisoner was unlawfully denied parole going back to January 1, 1998, when the Parole Board adopted their unconstitutional rules.

THE LACK OF INDEPENDENT CHECKS AND BALANCES

ENCOURAGES AND ALLOWS JUDGES TO ABUSE, POWER

Ostensibly, there are three ways to hold the Judge and Justices accountable: (1) Judicial Inquiry & Review Commission; (2) impeachment, and (3) criminal civil rights prosecution. Goodman unsuccessfully tried all three methods. The Judicial Inquiry & Review Commission refused to investigate, and he received no response to his petition for impeachment filed in the Virginia House of Delegates or the criminal civil rights complaint filed with U. S. Attorney Kavanaugh in the Western District of Virginia.

JUDICIAL REFORM, ACCOUNTABILITY, AND TRANSPARENCY ACT

The government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government

of laws, and not of men. It will not

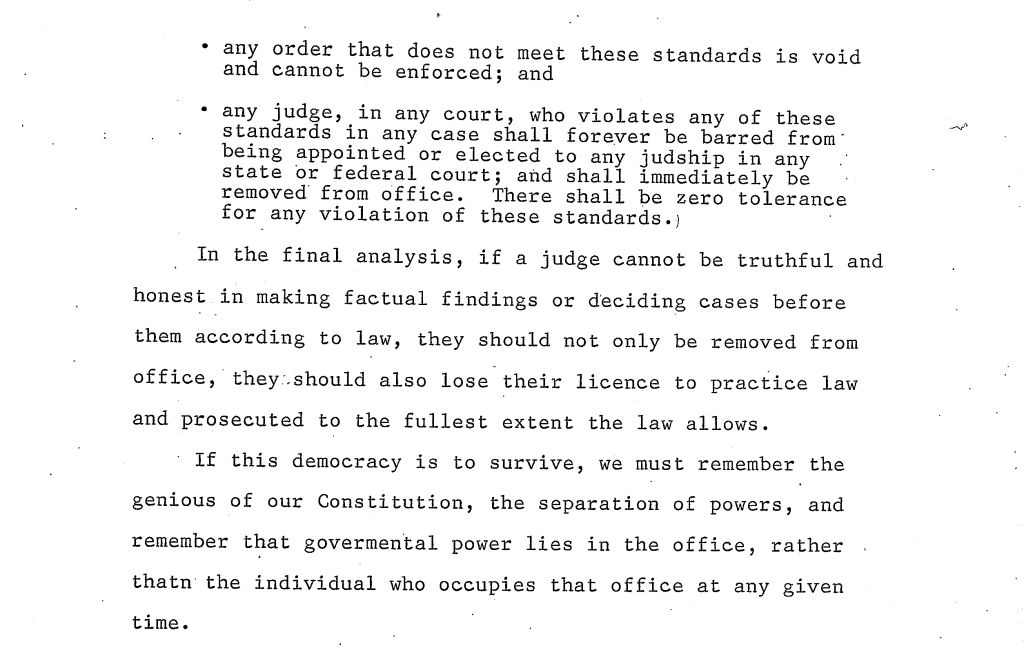

- any order that does not meet these standards is void and cannot be enforced; and

- any judge, in any court, who violates any of these standards, in any case, shall forever be barred from being appointed or elected to any judgeship in any state or federal court; and shall immediately be removed from office. There shall be zero tolerance for any violation of these standards,

In the final analysis, if a judge cannot be truthful and honest in making factual findings or deciding cases before them according to law, they should not only be removed from office, but they should also lose their license to practice law and be prosecuted to the fullest extent the law allows.

If this democracy is to survive, we must remember the genius of our Constitution, the separation of powers, and remember that governmental power lies in the office, rather than the individual who occupies that office at any given time.